This post is a WIP as I work through the project!

Years ago, I bought a very cozy heated blanket, that is, of course, internet connected. Why? Who doesn’t want to be told they can’t use their simple device because of a forced firmware update. Anyway, I never thought too much of the device, and it’s served me well all these years. Now, in my continued quest of “how lazy can I be?” I have decided that it is just too much effort to find the small control panel (it gets stuck behind the couch sometimes!) and turn on/off the blanket or fiddle with its temperature setting. After all, wouldn’t it be more useful if I could just do it from my phone?

Initial Poking Around #

I connected the blanket to my WiFi via the official app, and then started pulling it apart in JADX. After a lot of CTRL+F’ing, I found some interesting keywords, namely “listenUDP”, which looks like it starts up some socket for API calls (TuyaNetworkInterface.listenUDP(6667);). I did some more pivoting off that, by poking around the TuyaNetworkInterface, and then seeing that most of its implementation is in TuyaNetworkApi. The nice thing about TuyaNetworkApi is that it’s actually defined in a shared-object file packaged with the app. I’m much more comfortable ripping apart some C code than I am Java (the enterprise format is an unfortunate blindspot in my reverse engineering skillset).

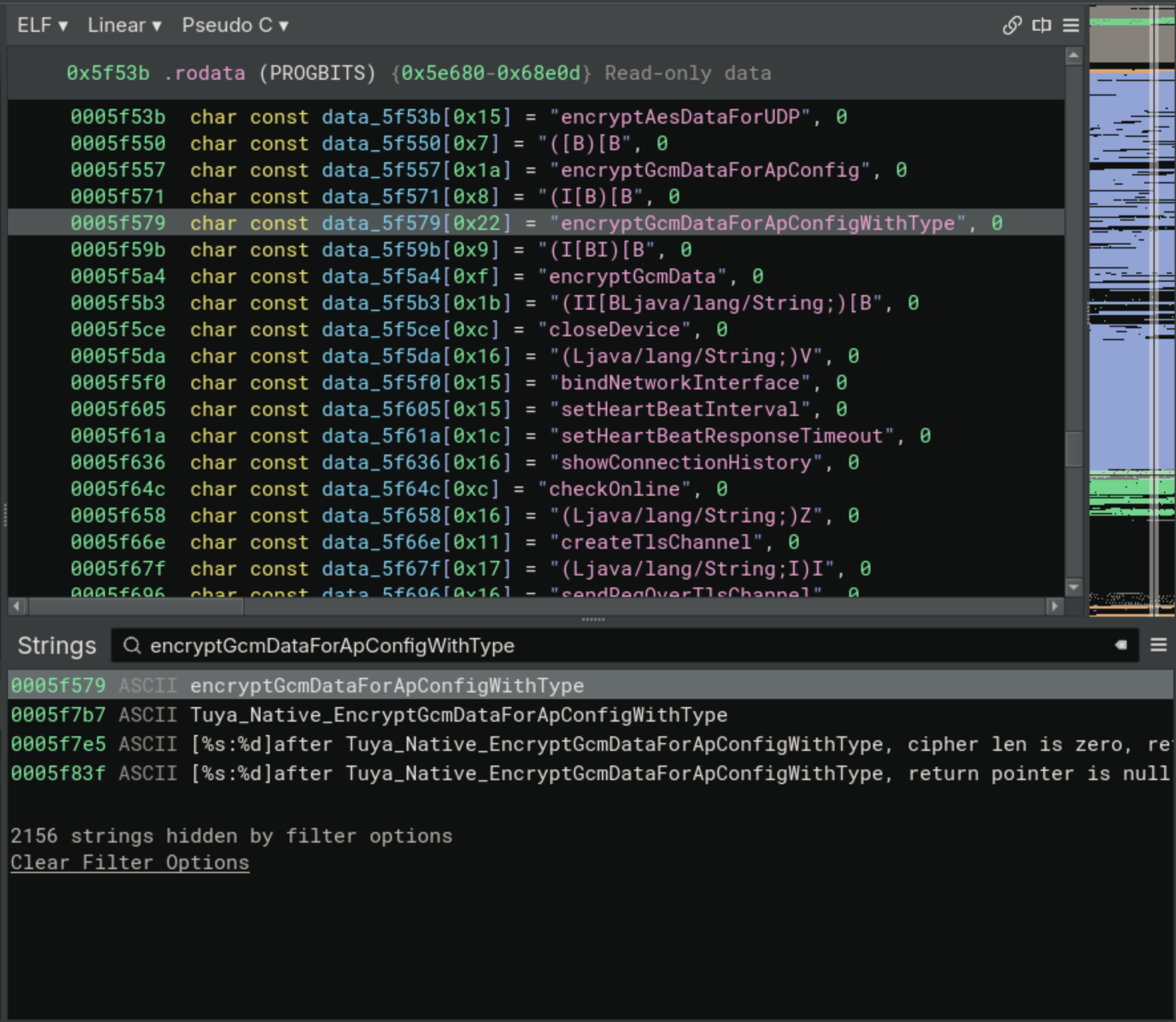

I’ll start by figuring out which shared-object file in the APK exposes the functions in the TuyaNetworkApi class, by just grep‘ing in the directory for a unique sounding function name (encryptGcmDataForApConfigWithType looks unique 🙂). You can see below I actually checked a few different function names, the first result came back with libnetwork-android.so which to me felt like a generic library, and not something specific to this app. So I tried a few different functions, and they all point to libnetwork-android.so, so let’s open it up in Binary Ninja!

╭─user@debian ~/Desktop/HeatedBlanket/decompiled/resources/lib/arm64-v8a

╰─$ grep -lir 'encryptGcmDataForApConfigWithType' .

./libnetwork-android.so

╭─user@debian ~/Desktop/HeatedBlanket/decompiled/resources/lib/arm64-v8a

╰─$ grep -lir 'setHeartBeatResponseTimeout' .

./libnetwork-android.so

╭─user@debian ~/Desktop/HeatedBlanket/decompiled/resources/lib/arm64-v8a

╰─$ grep -lir 'enableDebug' .

./libTYAvLogSDK.so

./libnetwork-android.so

╭─user@debian ~/Desktop/HeatedBlanket/decompiled/resources/lib/arm64-v8a

╰─$ grep -lr 'sendCMD' .

./libnetwork-android.so

JNI Reverse Engineering #

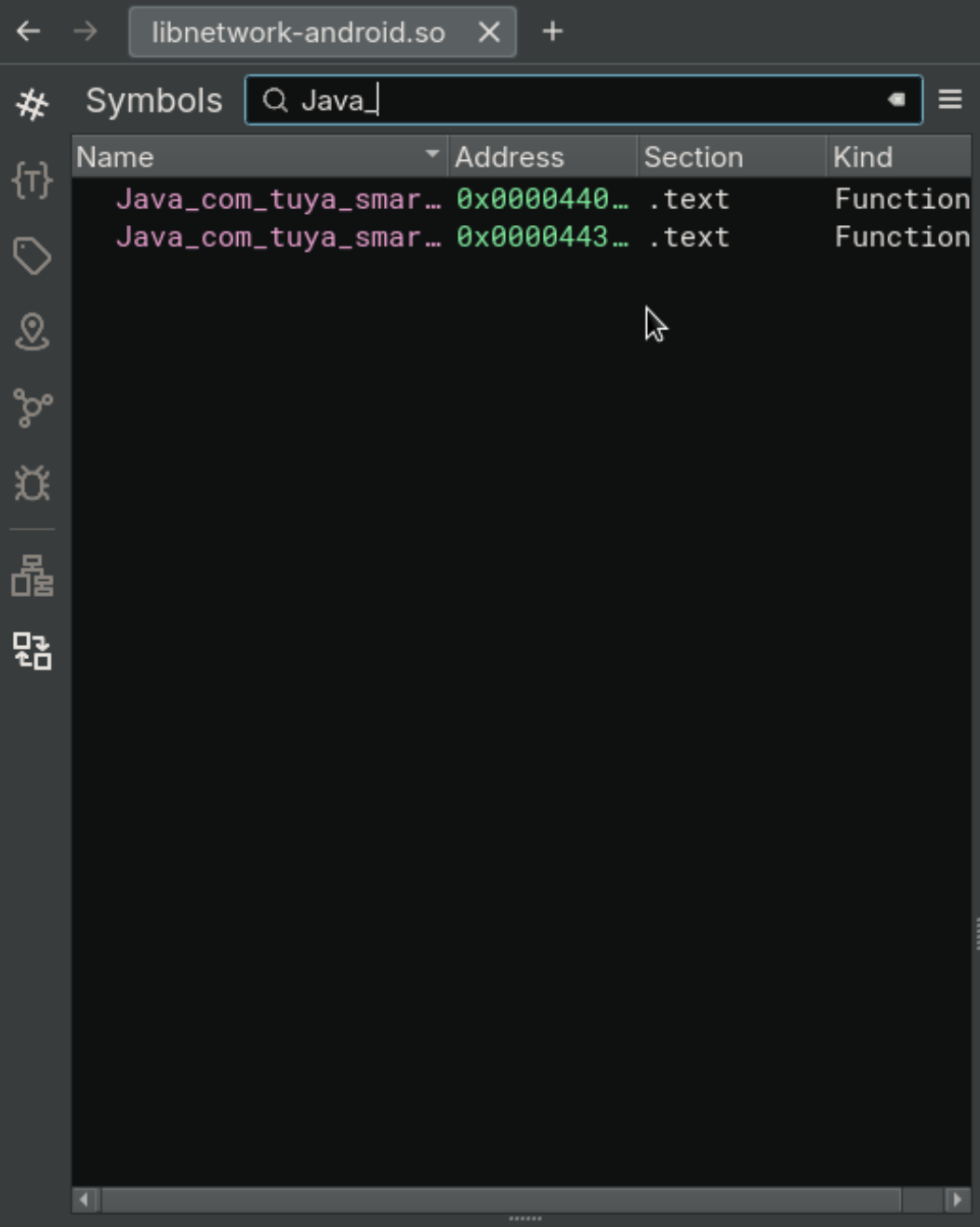

I opened up the file in Binary Ninja, and searched for Java_ in the symbols window, but didn’t find what I expected. I know that JNI functions that auto-magically resolve should start with Java_ followed by name of the Java package (delimeted by underscores rather than dots), but only two functions appear for this (first image, below): sendBroadcast and stopBroadcast. I expected to see the function names that I grep‘ed for but they only exist in the shared-object as a string (second image, below).

I am vaguley familiar with the substrings in around the function name, it’s the JNI Name Mangling (similar to C++’s mangling to encode return/parameter types). After pouring through JNI internals for hours finding a good StackOverflow post, I realized learned that I also have to track down the functions that are parsed in the JNI_OnLoad function. The StackOverflow post points to a Java documentation page that tells me I should interpret the memory in the previous image as an array of structures that gets passed to RegisterNatives, like so:

typedef struct {

char *name;

char *signature;

void *fnPtr;

} JNINativeMethod;

So, I looked at the data structure to find the beginning of the array, and found it at 0x5f301. Then I realized I can probably just get the address from whatever is passed into RegisterNatives (the signature takes a pointer to JNINativeMethod[]: jint RegisterNatives(JNIEnv *env, jclass clazz, const JNINativeMethod *methods, jint nMethods);). Of course though, it can’t be that easy! The binary seems to be a little more complicated than boilerplate code, not obfuscated (unless you consider C++ obfuscation, in which case you might be onto something), just a lot. I found this useful Android documentation page which explains the usage of RegisterNatives a bit more, but unfortunately, it looks like our JNI_OnLoad function isn’t getting any pretty resolution into what exactly is going on:

uint64_t JNI_OnLoad(int64_t* arg1)

{

int0_t tpidr_el0;

uint64_t x21 = _ReadStatusReg(tpidr_el0);

int64_t x8 = *(uint64_t*)(x21 + 0x28);

char const* const x2_1;

int64_t x4_1;

if (!(*(uint64_t*)(*(uint64_t*)arg1 + 0x30))())

{

int64_t* var_40;

if (!(*(uint64_t*)(*(uint64_t*)var_40 + 0x30))())

goto label_373c4;

if ((*(uint64_t*)(*(uint64_t*)var_40 + 0x6b8))())

{

x2_1 = "[%s:%d]Register Native Method Fa…";

x4_1 = 0x596;

goto label_373c0;

}

data_7c3a0 = arg1;

if (*(uint64_t*)(x21 + 0x28) == x8)

return 0x10006;

}

else

{

x2_1 = "[%s:%d]JNI_OnLoad Failed";

x4_1 = 0x58d;

label_373c0:

__android_log_print(6, "Tuya-Network", x2_1, "JNI_OnLoad", x4_1);

label_373c4:

if (*(uint64_t*)(x21 + 0x28) == x8)

return 0;

}

__stack_chk_fail();

/* no return */

}

Presumably, arg1 is a pointer to the JavaVM structure, which makes arg1+0x30 probably the GetEnv member (assuming that the structure in this doc is correct) - which perfectly matches the Android documentation page. I found that the JNIEnv* (the output of JavaVM->GetEnv) is actually a typedef to JNINativeInterface*, which we can view here. Assuming var_40 in the above decompiled code is the JNIEnv* (I should probably actually get all this type resolution to work, but whatever), then JNIEnv* + 0x30 is FindClass (score! This, again, matches the Android doc page), and JNIEnv* + 0x6b8 is SetFloatArrayRegion, which … doesn’t sound right. On that page RegisterNatives would be JNIEnv* + 0x6d0 which isn’t too far off, and I’m willing to accept just a change in the header file (god knows how old this shared-object is).

At this point, I know I need to clean up the function, which means giving all of those arg1 and var_40 variables a real type. I googled around and found someone already made a header file with JNI types, so I was able to import that into Binary Ninja. Here is what the function looks like now:

jint JNI_OnLoad(JavaVM* vm, void* reserved)

{

int0_t tpidr_el0;

uint64_t x21 = _ReadStatusReg(tpidr_el0);

int64_t x8 = *(uint64_t*)(x21 + 0x28);

JNIEnv* penv;

char const* const x2_1;

int64_t x4_1;

if (!(*(uint64_t*)vm)->GetEnv(vm, &penv, &data_10006))

{

JNIEnv* env = penv;

jclass clazz = (*(uint64_t*)env)->FindClass(env, "com/tuya/smart/android/device/Tu…");

if (!clazz)

goto label_373c4;

JNIEnv* env_1 = penv;

if ((*(uint64_t*)env_1)->RegisterNatives(env_1, clazz, &data_7c008, 0x20))

{

x2_1 = "[%s:%d]Register Native Method Fa…";

x4_1 = 0x596;

goto label_373c0;

}

data_7c3a0 = vm;

if (*(uint64_t*)(x21 + 0x28) == x8)

return 0x10006;

}

else

{

x2_1 = "[%s:%d]JNI_OnLoad Failed";

x4_1 = 0x58d;

label_373c0:

__android_log_print(6, "Tuya-Network", x2_1, "JNI_OnLoad", x4_1);

label_373c4:

if (*(uint64_t*)(x21 + 0x28) == x8)

return 0;

}

__stack_chk_fail();

/* no return */

}

Pretty nice! I should’ve done that from the start, but what can I say? I told you at the beginning I’m lazy 😉. Now, I was able to go back to the memory region that contained the JNINativeMethod array, and define it as such - it’s much prettier.

Understanding the App Logic #

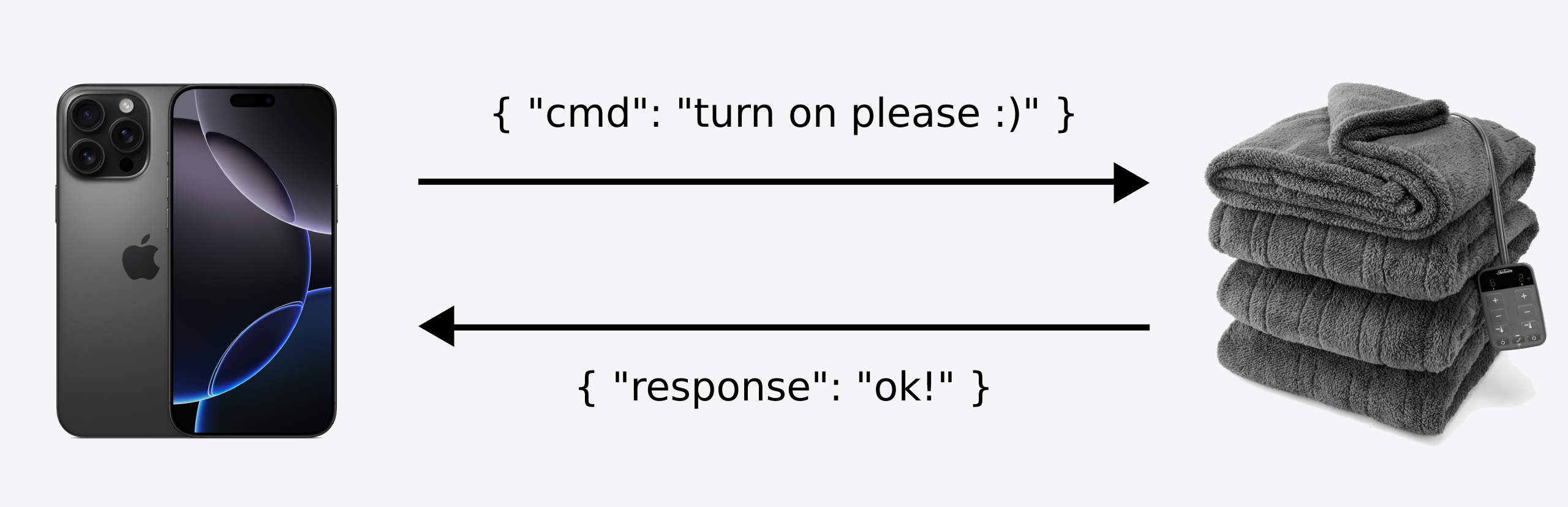

Now that we have the core functionality of the device in front of us (well, I assume to be honest, this might be a red herring), let’s actually go about and change the temperature of this blanket! The first function that jumped out at me was sendCMD. I’d love for this just to be some socket listening for JSON or something like that.

And shocker - it wasn’t anything close to that easy. The function is massive, it has a lot of C++ objects, etc. Since this is supposed to be a quick, two-day project (thank you OPM for the two back-to-back snowdays 🙏), I’m going to try a few different approaches before committing to this static RE process. First, I think I’ll take a look at other shared-objects in the folder and see if any functions defined in them are promising. Executing find . -name '*.so' -exec sh -c "echo '>>>>>>> '{}; readelf --wide --demangle --symbols {} | grep -v UND" \; > ~/Desktop/HeatedBlanket/symbols.txt outputs all of the symbols (demangled!) for all of the files in the directory (at that point I was in resources/lib/arm64-v8a from the JADX output).

I started by looking at all of the shared-object files with “tuya” in the name, as I figure based on the Java classes this is either the company or project name. This yielded some interesting results, and unfortunately, a lot of not-so-interesting results. They seem to statically compile OpenSSL into all of their binaries, which just means there is a lot of repetition. Reading through some of the more interesting function names, I slowly came to the (unfortunate) realization that this app probably did nothing special. It looks like tuya is an IoT services company that does all of the “cloud-connected” pieces of having an IoT product. So the app talks to the Tuya SDK that comes bundled, which brokers with the Tuya servers to talk to the blanket.

My next steps are: scan the device and see if anything interesting comes up, and use a proxy to see what types of commands my phone sends and the devic

Scanning the Device #

What happened when I tried to nmap the blanket is kind of hilarious. I set off to do my typical nmap scan, but nmap complained “Note: Host seems down. If it is really up, but blocking our ping probes, try -Pn.” That’s odd, I know I have definitely pinged this device before… I tried to manually ping it again, and now my pings are getting blocked! I confirmed on the router that the device was still connected, and to the IP I was using, and the app didn’t return any errors like it couldn’t reach the device. I checked the small display/control panel on the blanket itself and it displayed a small “🛜” symbol to show that it was connected, and that the blanket heater was currently off. I told myself “No way…”, turned on the blanket heater to the lowest setting, returned to my computer and tried to ping it. And, of course, the pings work now. So starting 2025 off with a strong contender for “Most Cursed Sentence”: My blanket will only respond to ICMP Ping requests when its heater is on. Or, as I told my friend, “Give it a minute, the netstack just has to …. warm up (•_•) / ( •_•)>⌐■-■ / (⌐■_■)”

Anyway! I scanned the device and it came back with one open port:

╭─axelpersinger@Axels-MacBook-Air ~

╰─$ sudo nmap -p- -sV -sS -O --stats-every 5s 10.0.0.216 | tee ~/Desktop/nmap.txt

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

6668/tcp open tuya Tuya IoT protocol

1 service unrecognized despite returning data. If you know the service/version, please submit the following fingerprint at https://nmap.org/cgi-bin/submit.cgi?new-service :

SF-Port6668-TCP:V=7.95%I=7%D=1/7%Time=677D406E%P=arm-apple-darwin24.1.0%r(

SF:GetRequest,B6,"\0\0U\xaa\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\x08\0\0\0K\0\0\0\x003\.3\0\0\0\0

SF:\0\0j\x16\0\0\0\x01{\xd39\x98\x05\x8b\xbe\xc7#W\]\x1f\x9a\xc9\+Gu\x94\n

SF:\xc7\xed\xf7\x9f\xe9\xf5\0\xad\xddk\x1ew\xf6\xca\x1b\xa7\x15\xb6&1\xba\

SF:xed\x1e=\xff;w\x7f\xa3<\xf4\xd2<\0\0\xaaU\0\0U\xaa\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\x08\0\

SF:0\0K\0\0\0\x003\.3\0\0\0\0\0\0j\x17\0\0\0\x01\x88RPGgG\x06\xad\xb3\x9b\

SF:x92\xff\x91P2Nu\x94\n\xc7\xed\xf7\x9f\xe9\xf5\0\xad\xddk\x1ew\xf6AZ\x8e

SF:x\xd5\xd8}\xf2\xf1\x8d\x1bt\xfc\x92\xcb\x18\*u\x8b\.\0\0\xaaU");

MAC Address: 50:8A:06:64:9F:E5 (Tuya Smart)

Device type: specialized

Running: lwIP

OS CPE: cpe:/a:lwip_project:lwip

OS details: lwIP 1.4.1 - 2.0.3

Network Distance: 1 hop